Don’t lose your balance

6th May 2020

Most of the time – thankfully – we don’t have to worry about navigating a crisis. Most of the time financial markets get by, tackling relatively benign, transient obstacles. Occasionally however, as we have experienced with the ongoing coronavirus crisis, the challenge can appear more daunting. It is a useful moment to step back and consider best practice.

Drawing on Greek mythology, Homer’s The Odyssey captures the importance of preparedness. During his ten-year journey back home following the Trojan wars, the hero Odysseus is told he would encounter dangerous sea creatures called Sirens. With their sweet songs, and promises of great wisdom, the Sirens would try to lure him into the water to his death.

To avoid his fate, Odysseus ordered his crew to plug their ears with beeswax and tie him to the ship’s mast. On hearing the Siren’s song, Odysseus begged to be untied but the crew refused his pleas. Unable to act on his urges, the ship sailed safely past the danger but only thanks to its captain knowing how decisions made ‘on impulse’ can be counterproductive and preparing his crew accordingly.

The challenge for investors is that during times of crisis there are Sirens circling everywhere, luring us towards making bad decisions.

If ever there was a more relevant truth about investing it is that there will be turbulent periods in the long, meandering life of an investment portfolio. It is one of the reasons we have spent the last three crisis-free years writing about ways to deal with the occasions when things don’t go to plan.

We know that it pays to set clear objectives, to keep focused on the long term, to stay unemotional, and to expect unforeseeable events over the coming years. But when markets are volatile, how can we ensure our investments – as well as our emotions – remain on the right track?

Asset allocation

Central to the discussion is the concept of ‘asset allocation’ in a portfolio, which is essentially the combination of different types of investments. Two of the most common portfolio components are equities (shares) and bonds.

The mix of these assets in a portfolio has the biggest influence on the overall risk and return profile. Recognising this, we analyse the expected level of return and risk of a wide range of asset types (including equities and bonds), both individually and when they are combined. It helps us construct optimised investment strategies which seek to maximise the returns at different levels of risk.

Say we have constructed a simple portfolio comprising 50% equities, 50% bonds. At any point in time it is impossible to predict which of these assets will perform better than the other (hence why we diversify). But what we have observed is that over the long-term equities have demonstrated higher levels of return (and risk).

Therefore, over the long-term, we would expect the equity portion of our portfolio to grow in excess of the bond allocation – for instance, from a 50/50 split to say 60/40.

Portfolio drift

At first glance, owning a growing allocation to equities over time seems like it could be a good thing for performance. However, as the equity allocation grows, so does the overall risk level. A portfolio which is over-allocated to equities at the start of a market downturn, such as in the first quarter of 2020, will typically experience higher volatility than the investor might expect.

The inverse is also true, particularly following periods of weakness in financial markets. The 50/50 equity-bond portfolio could end up over-allocated to bonds, say 40-60. In this instance, the portfolio would be underinvested in equities and therefore fail to fully capture a subsequent rebound.

Rebalancing strategies

Problems can arise when volatility in the markets skews the desired asset allocation. Portfolios in perpetual misalignment are less likely to achieve their target risk and return. That’s why we pay close attention to the level of skew. When it is out of line, we undertake a process called ‘rebalancing’ to bring portfolios back in line with target.

Setting an appropriate threshold is the key to striking a balance between avoiding too much drift on the one hand and interfering too often on the other.

As a result of our analysis we use a combination of time-based and threshold-based rebalancing strategies.

Practically, that means we rebalance portfolios on a regular six-monthly schedule – regardless of market conditions – typically in February and August each year. In addition, we overlay a threshold which triggers a rebalance when portfolio allocations are misaligned by 3% or more.

Back-testing this approach over the last 14 years we see that the 3% threshold is triggered infrequently but at significant moments: during the 2008 financial crisis, in the 2011 European sell-off, and recently in the 2020 coronavirus crisis. The semi-annual rebalancing schedule keeps allocations on track in the interim.

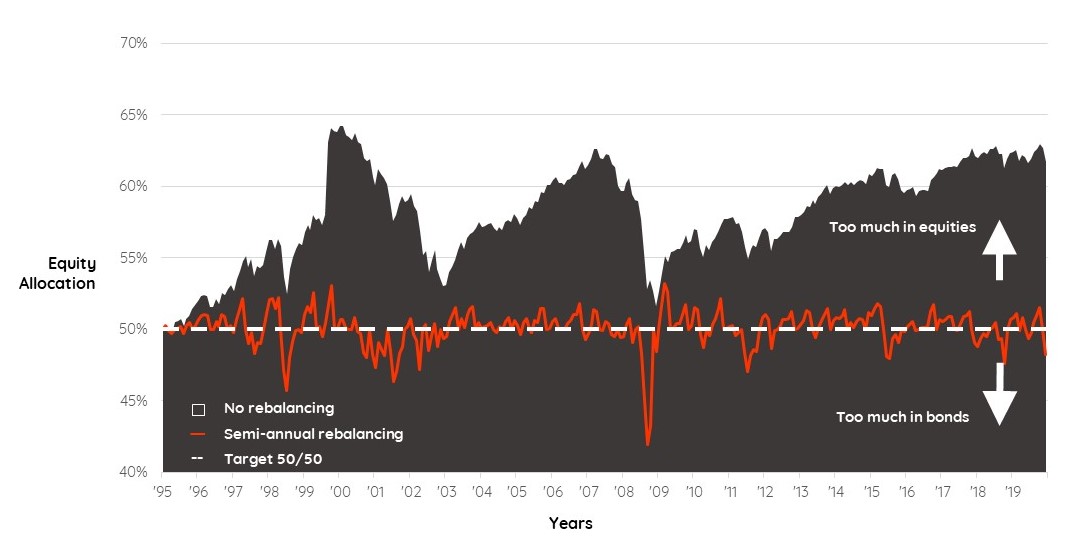

The chart below illustrates, using real historical data, the degree to which a non-rebalanced portfolio can drift away from its target. Looking back from 1995 to 2020, the dark shaded area shows the equity allocation in a 50/50 equity and bond portfolio which is left untouched. The red line illustrates the drift of a portfolio rebalanced every six months, while the white dashed line represents our 50% equity target.

Starting from 1995, the equity allocation rises from 50% to just under 65% in less than five years. The year 2000 brings with it the dotcom crash, setting off three years of equity market declines. Without any rebalancing, the portfolio is over-allocated to equities at the start and is therefore taking far too much risk compared to the target.

The picture is similar in the years since the 2008 financial crisis, with the no-rebalance portfolio experiencing equity allocations between 60-65% for half a decade before coronavirus hits.

The red line on the other hand shows how regular rebalancing keeps the asset allocation on a relatively even keel throughout the last 25 years. Equity allocations remain anchored to the long-term target.

The primary aim of rebalancing is risk management. By bringing the risk level back to an acceptable level, investors have a better chance of sticking to their plan, enduring market slumps, and being in a better position to meet long-term financial objectives.

Realigning the equity and bond allocations also has a secondary benefit: ensuring we are consistently buying low and selling high. After the markets experience a dislocation like that resulting from the coronavirus, a rebalance will mean selling the assets which have performed relatively better (i.e. bonds) and buying the assets which are now comparatively cheaper and under-allocated (equities).

It took him time, but Odysseus made it home thanks to the pre-emptive measures put in place and the cool head of the sailors around him. Keeping your balance during turbulent markets requires the same: a long-term perspective underpinned by tools like clear objectives and a defined rebalancing policy.

Looking at the status of the coronavirus crisis today, it seems the ship has steadied but the outlook remains obscured. We think investors should not be surprised to see more Sirens circling in the short term. Prepare to tie yourselves to the mast.

The above chart uses monthly data sourced from Morningstar, April 1995 to March 2020. Equities are represented by the FTSE World Total Return index. Bonds are represented by the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Total Return index.

Contact us to see how we can help.

+44 (0) 20 7287 2225

hello@edisonwm.com

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The information contained in this website does not constitute advice. The FCA does not regulate tax advice. The FCA does not regulate advice on Wills and Powers of Attorney. The Financial Ombudsman Service is available to sort out individual complaints that clients and financial services businesses aren’t able to resolve themselves. To contact the Financial Ombudsman Service please visit www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk.