Are we nearly there yet?

15th February 2019

Around this time last year, the immoderate Elon Musk fired his Tesla Roadster into space. The cherry red sportscar, strapped to the front of the 1,400 tonne Falcon Heavy rocket, acted as a dummy payload for future missions to space. Its final target was to enter a ‘low energy elliptical orbit’ around the sun. Today, Musk’s motor is in an orbit of sorts, hurtling through the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter at 75,000mph.

Back on earth, the recent Christmas season meant many will have enjoyed their own post-turkey ‘low-energy orbits’ around Britain’s motorways as they travelled between family and friends. And now the New Year offers a ripe opportunity to focus the mind on what we want to achieve in 2019 and beyond – interplanetary or otherwise.

The late US investor and commentator Ralph Seger observed that “an investor without investment objectives is like a traveller without a destination.” We agree that having objectives matters. After all, how many festive motorists will have set off without knowing where they wanted to end up? If we don’t know where we want to get to and when we want to get there, we can’t possibly plan the journey. It is the same with investing.

An investor without investment objectives is like a traveller without a destination

In our metaphorical investment journey, speed is a bit like risk and the distance travelled is return. Once you know where you’d like to get to and when, you can work out how fast you’ll need to go and whether you’ll be comfortable travelling at that speed. Set off too slowly and you won’t reach your destination in time. Set off too quickly and you might crash or abandon your journey because the ride is too scary.

All too often, investors choose a level of risk without relating it to the investment objective. Returning to the car journey analogy, that’s a bit like deciding to go for a drive at 10mph or 80mph straight out of the drive without deciding on a direction. No one does that.

Edison adopts a scientific approach. We model the investments allocated to each objective, including the effect of income, expenses, tax and investment performance to calculate the return required and its associated risk. And once you know what level of return (and risk) is required, you can work out whether you’d be comfortable with it.

What level of risk you’re comfortable with is a personal choice. But for any investment strategy the overall timescale and the frequency you review your investments are important considerations.

The riskier an investment is, the more it fluctuates day by day. However, over long periods of time, these fluctuations normally even themselves out. As a result, reviewing investments every day is going to feel very different to reviewing them once a year.

Similarly, on average, riskier investments perform better over time than cautious investments. Longer timescales allow time for the ‘law of averages’ to play out. Over a two-year period, our adventurous strategy has outperformed our cautious strategy 60% of the time. Over a five-year period, that rises to 75%.

Riskier investments have a broader range of possible outcomes

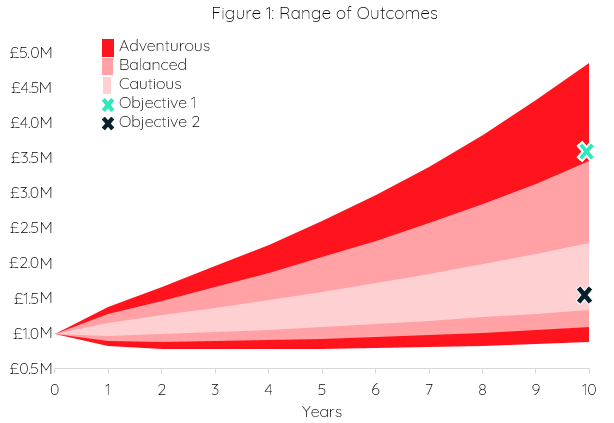

In Figure 1 below, each shaded area represents the hypothetical range in performance (from the very best to the very worst) of an adventurous (bright red) to a cautious portfolio (lightest red). Although the riskier adventurous approach is likely to perform better on average, the range of possible outcomes is greater. We can use this to illustrate the marriage between risk (the shaded ranges) and objectives (the green and black X markers).

Objective 1, the green X, requires us to turn our starting £1M of savings into £3.5M after 10 years. It’s clear that the cautious approach won’t get us near. The balanced approach wouldn’t quite get us there either.

Only the adventurous approach gives the investor a reasonable chance of achieving this objective, albeit with the risk of greater downside. There is no point aiming for this objective with a cautious approach. If the investor is not comfortable with an adventurous approach, then perhaps the objective needs to change.

Objective 2 requires our £1M to grow to £1.5M in 10 years’ time. This objective is within the ranges of all the strategies shown. In this case, it makes sense to adopt a cautious approach because they can be very confident of achieving the objective with a low risk approach. There is no point taking the additional risk of an adventurous approach as it does not give any greater chance of achieving the objective.

When faced with this scenario, we find that some more adventurous investors can feel disappointed. They like their investments to ‘work hard’ and are comfortable with them rising and falling in value considerably. To them a cautious strategy is, well, boring.

There’s nothing wrong with getting a thrill out of your investments but it doesn’t make sense to put your ‘real objectives’ at risk in the pursuit of investment thrills. If the pursuit of thrills is important, it makes more sense to ring-fence some ‘speculation’ money which can be invested adventurously. That way, all investments remain aligned with their objectives.

It is vital not to lose track of where your investments need to end up. “Higher performance” alone is not a real investment objective. Real investment objectives have a timescale and cost.

‘Higher performance’ alone is not an investment objective

So how do we know if our investments are ‘doing well’? The traditional method is to use benchmarks. Benchmarks are usually market-based comparators that give an idea of how similarly-invested portfolios have fared. They’re normally based on investment indices which track the average performance achieved in different countries, asset classes, industry sectors or by a group of managers.

There are over three million indices in the world today, tracking everything from small Chinese companies to the largest 500 companies in America, so picking the most appropriate one can be difficult.

A well-chosen benchmark can be useful to assess how you are performing versus other managers, but they don’t help assess whether you’re on target to meet your objectives. As drivers, we wouldn’t look out of the window at all the other cars to assess whether we’re on the right course. The chances are that the other cars all have different destinations.

That’s why we always use target returns to assess progress towards investment objectives. Having a specific target is like using a financial sat-nav; they are unique to each individual investor, keeping them travelling in the right direction at the right speed.

Investment targets are financial sat-navs

Clear goals and measurable targets are the cornerstones of effective long-term investing. Without them, it is almost impossible to plan and monitor performance. They effectively counter behavioural bias, guiding investors away from greed (chasing higher returns) and fear (not taking enough risk). Hence, targeting goals makes it easier to remain a disciplined investor and help us answer the age-old question, “are we nearly there yet?”.

…

If this has piqued an interest, we previously explored the link between investing and the biology behind instincts, impulses and emotions in our piece on staying unemotional.

Important Information

If you have any questions on the above or to find out more about our investment service, please call 020 7287 2225 or email hello@edisonwm.com.

This document does not constitute advice.

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future.

All the performance data used in this report has been sourced from Morningstar and investment performance is calculated using Time Weighted Return. Performance data for the above investment strategies is shown since inception on 01 April 2007. Therefore, the ‘07 performance figures do not cover a full calendar year.

Figure 1 is hypothetical and for illustrative purposes only. It represents a fictitious spread of returns for a Cautious, Balanced and Adventurous investment strategy over a ten year period.

Edison Wealth Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. The company is registered in England and Wales and its registered address is shown above. The company’s registration number is 06198377 and its VAT registration number is 909 8003 22. This document does not constitute advice.

Contact us to see how we can help.

+44 (0) 20 7287 2225

hello@edisonwm.com

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The information contained in this website does not constitute advice. The FCA does not regulate tax advice. The FCA does not regulate advice on Wills and Powers of Attorney. The Financial Ombudsman Service is available to sort out individual complaints that clients and financial services businesses aren’t able to resolve themselves. To contact the Financial Ombudsman Service please visit www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk.