The trouble with ERI

27th January 2020

HMRC’s Wealthy and Mid-sized business unit has been sending out letters to high net worth individuals regarding investments in offshore funds. HMRC suspects that there is widespread lack of awareness of how income from offshore investments should be reported. Various disclosure campaigns have alerted HMRC to the scale of the problem.

Our own experience indicates this may be true, partly because the information has not been easily accessible by investors. Failure to include offshore income on tax returns can attract severe penalties. It is important that investors understand their exposure to offshore investments and how the tax consequences could impact on their choice of funds.

Action to take

An HMRC spokesperson told Accountancy Daily: ‘Ensuring the correct UK tax is paid on offshore investment funds can be complex. This activity is to help people with complex affairs make sure that they have paid the right amount of tax at the right time.’

This starts with understanding whether there is exposure, to what extent and dealing with the potential liability. All of this will depend partly on the type and reporting status of the offshore investments held.

For any advice or guidance on offshore funds, please don’t hesitate to contact one of our investment managers or financial planners at Edison. We will be happy to answer questions on this topic and help where we can.

Reporting and Non-Reporting Offshore Funds

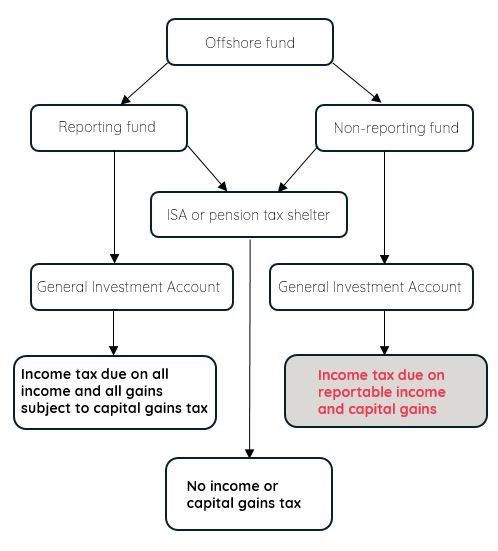

In 2009, new legislation was introduced which gave offshore funds one of two statuses: reporting or non-reporting funds. Reporting funds have certain HMRC obligations and are treated in a simpler way than non-reporting funds.

An investor in an offshore reporting fund is subject to income tax on any income arising in the fund regardless of whether it is distributed or not. An investor in a non-reporting fund is only subject to tax on income which is distributed to them.

Excess Reportable Income (ERI)

Income received by a reporting fund but not distributed to the investor is called Excess Reportable Income (ERI). The investor is liable to income tax on ERI accrued. It is their responsibility to report ERI on their tax return and pay any tax that may be due.

The trouble with ERI

Prior to the introduction of the Common Reporting Standard (CRS), which gave HMRC unprecedented access to offshore investments, very little was written about ERI, placing it very much in the domain of tax professionals and experienced investors. There has also been little incentive for the fund management industry to alert investors, or even spend the time and resource in making ERI information clear and accessible.

At Edison, we manage both offshore and onshore portfolios, depending on our clients’ needs. We have always included ERI data as part of our annual tax reporting packs. Our experience of accessing ERI data from fund managers has been mixed. And that is the same for investment platforms and custodians.

Overall, it is not surprising that private or less experienced investors find it difficult to access ERI data, let alone use it correctly. Firstly, investors are often unaware of ERI. Secondly, they often think it does not apply to them anyway, notably when their portfolios are held onshore.

They should keep in mind:

- Most of the information is available online on the fund manager’s website but may not be obvious.

- Accumulation funds (where income is re-invested rather than paid out), or Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), still generate income.

- It impacts basic rate taxpayers.

- To check where the investment fund, or ETF is domiciled – they may have just the one offshore holding in a portfolio of otherwise UK domiciled funds.

For example, commonly recognised iShares ETFs are domiciled in Ireland albeit available on all the usual UK investment platforms. Or Schroders, another widely recognised name to UK investors, has funds such as the ISF UK Equity fund. Despite sounding like a ‘very UK’ fund, it is actually domiciled in Luxembourg.

HMRC define offshore funds very broadly, a definition which captures unit trusts, companies, investment partnerships and even contractual agreements, domiciled outside of the UK.

Finding the information

Whilst fund management groups have reporting obligations to the investor (and the regulator), they have no responsibility for ensuring those investors are tax compliant. It is up to the investor (and/or their agents) to find the relevant information. Fund managers typically make ERI available on their websites, but our experience is that some websites are easier to navigate than others!

Even if an investor can obtain the correct information, it is not always obvious what they should do with it! For example, it is often not straightforward to work out which tax year each ERI falls into as it depends on the fund management group’s reporting period, which is not always aligned to the tax year. Investors also need to know when to apply Group 1 and Group 2 income!

At Edison, we include ERI as part of our tax packs but to do so requires considerable effort. Where information is not available on websites or other sources, the last recourse is to call fund management groups directly.

Tax liability

Since all income in reporting funds is subject to income tax, remaining compliant is that little bit easier. Ultimately though, income distributed from reporting and non-reporting funds is subject to the same income tax regime. The main difference to UK investors is the taxation of disposals.

Profits (i.e. increase in capital value) on reporting funds are subject to UK Capital Gains Tax (CGT), currently (19/20 tax year) at 20% (or 10% on any gain falling in the basic rate band). Profits on non-reporting funds are treated as Offshore Income Gains (OIGs) and subject to income tax of up to 45%.

The tax treatment of gains is important when it comes to offshore fund selection. For example, it may be more tax advantageous, at current CGT rates, to invest in a fund with reporting status where the fund’s investment objective is to deliver long term capital growth. Conversely, where the aim of a non-reporting fund is to maximise distributed income then the treatment of gains as income will, arguably, be less of a disadvantage.

The reporting status of a fund can change, and investors should check the status of the fund when preparing their tax return information. If a fund’s reporting status changes during the period it is held, any gains will be taxed as a non-reporting fund for the entire period of ownership.

Figure 1. The tax treatment of offshore funds

How we can help

If you have any questions on the above or to find out more about our financial planning service, please call 020 7287 2225 or email hello@edisonwm.com.

Important information

The above is a simplification of the legislation. It does not constitute advice. This piece was written based on the legislation applicable at the time. The views expressed above are subject to changes in legislation. The Financial Conduct Authority does not regulate tax advice.

<< Back to Insights

Contact us to see how we can help.

+44 (0) 20 7287 2225

hello@edisonwm.com

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The information contained in this website does not constitute advice. The FCA does not regulate tax advice. The FCA does not regulate advice on Wills and Powers of Attorney. The Financial Ombudsman Service is available to sort out individual complaints that clients and financial services businesses aren’t able to resolve themselves. To contact the Financial Ombudsman Service please visit www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk.