A decade of sustainable gains?

28th February 2020

We stand on the doorstep of a new decade. Before rushing to open the door, it’s worth pausing to make sure we have readied ourselves in the best way possible. After all, Greek philosopher Plato once wrote, “The beginning is the most important part of the work”. Two hundred and forty decades later, it seems a good opportunity to heed that advice.

What can we expect from the next ten years? And, as investors, how do we tread the path between frivolous crystal-ball gazing and carefully reasoned forecasting? To start, we might consider recent history – namely, what was the view from the doorstep a decade ago?

Recovery position

The world was in a fragile place in 2010, the memory of the financial crisis still fresh in the mind. Had we been writing a decade review back in 2010 it would have made for unpleasant reading. There were two separate recessions, the US stock market index (the ‘S&P 500’) fell 57% over the course of 17 months, whilst ending the 2000s 24% lower than where it began.

It’s no wonder that faced with a world in the grips of austerity investors had taken their money out of the markets, waiting for the outlook to improve. Heading into 2010, US unemployment hit nearly 10% and GDP growth remained inconsistent at best. “Bull Market Shows Signs of Aging”, was the headline in one US financial paper from December 2009.

But the global recession provided the backdrop to an impressive record-breaking recovery. As we saw, and have previously noted is often the case, the darkest years of the financial crisis were followed by years of consistent positive performance for the markets.

The ten years from 2010 to the end of 2019 have been dubbed the “decade of the bull” thanks to the largely uninterrupted upwards trajectory seen across many equity markets.

Few regions have been more impressive than the US; since 1926 there have been 13 distinct periods of “bullish” stock market growth (which is defined as any time frame without a 20% fall in the S&P 500). On average, those periods lasted for 53 months.

Today’s bull market, having begun in March 2009, ticked into its 129th month in December 2019. Investors fortunate enough to have some skin in the game have been rewarded with ten years of solid growth – with relatively little volatility – in the US, UK and other markets.

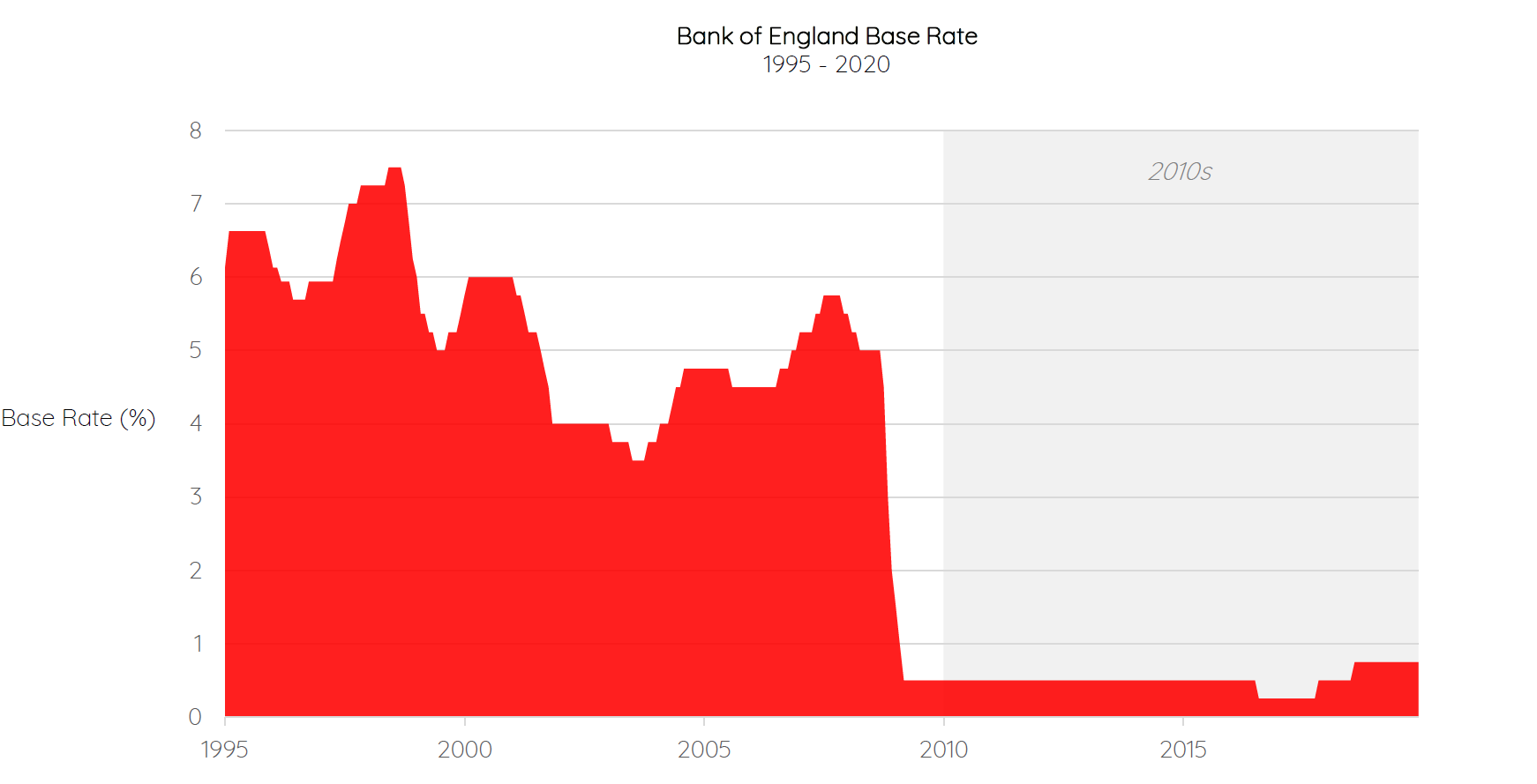

There is some debate over which were the active ingredients of success. Many economists point to monetary policy. Specifically, years of historically-low interest rates encouraged spending and a new era of “quantitative easing” (QE) pumped money into the economy through government bond purchases.

Rate cuts and QE fulfilled their purpose by making money cheap to borrow, incentivising loan growth and encouraging investors to recommit to the financial markets. The chart below shows just how unusual the low interest rate environment has been in the context of the past 25 years.

Large, coordinated efforts by global central banks to stabilise the economy have appeared to support financial markets. And what’s more, those efforts have defied predictions around hyper-inflation, a double-dip recession and uncertainty in the stock market.

Tech it or leave it

Central banks can’t take all the credit. The last decade saw a boom in one US sector that has driven stock market returns ever since.

Ten years ago mobile phones still had physical buttons. Early iPhone versions existed, but almost half of all handsets in the US were still made by Blackberry. Only 10% of users listened to music on their device and less than a third accessed the internet.

It’s true many could have predicted the growth of smartphones to continue, but few would have anticipated the impact of smart devices on so many areas of modern life.

The Wall Street Journal recently summarised the digital shift succinctly, saying that “first the mobile phone changed, then it changed us.” And with that change came the meteoric rise of new technology sectors. One swipe through the smartphone of 2020 will tell you which ones: transport (Uber), shopping (Amazon), communicating (WhatsApp), banking (Monzo), holidays (Skyscanner), fitness (Strava), films (Netflix) and music (Spotify), to name a few.

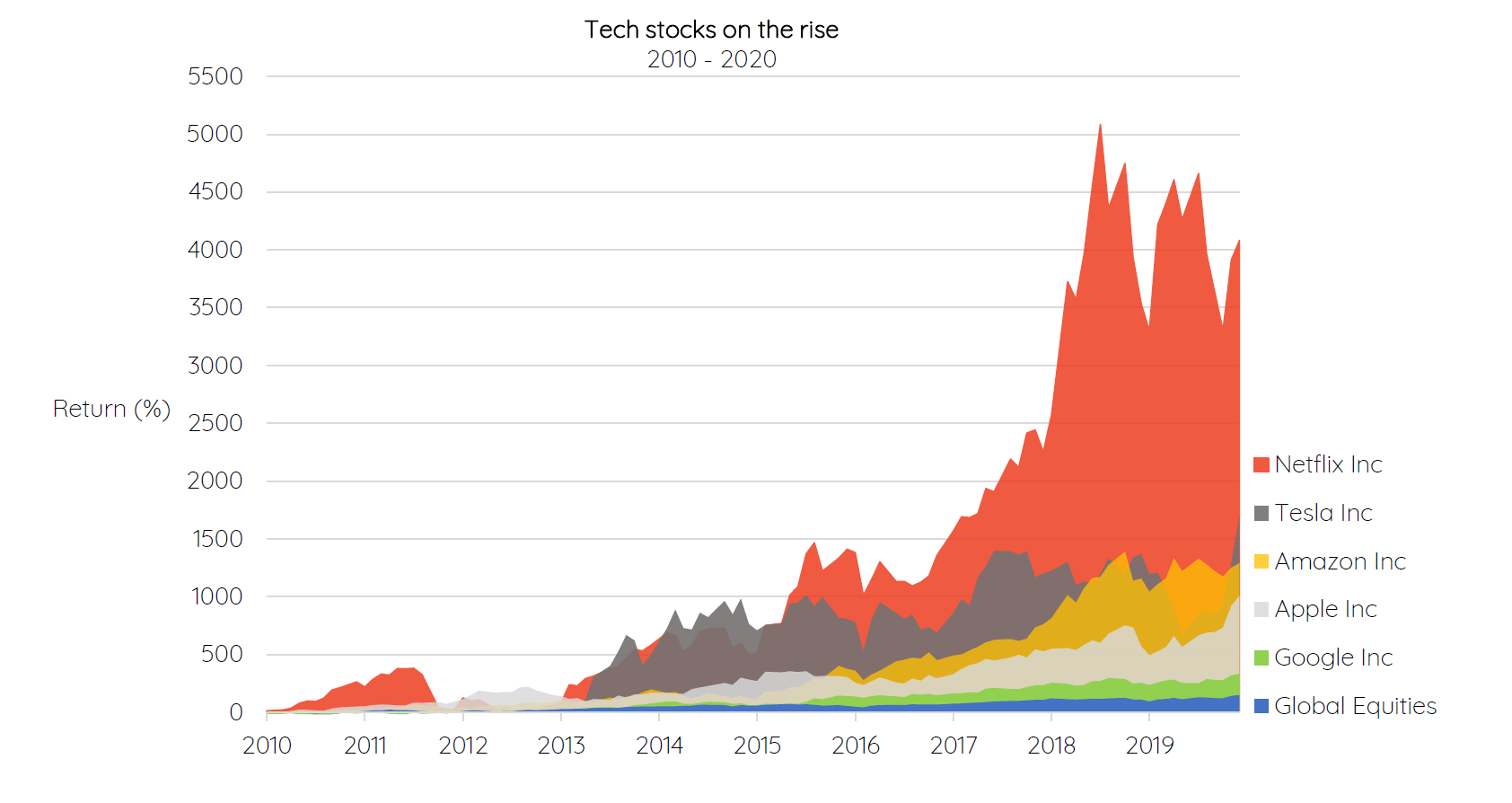

To demonstrate just how much some of these companies have grown over the last decade, we have plotted a selection in the chart below (some obvious candidates, like Facebook, have been excluded as they were still private firms in 2010).

In 2010, the largest stock in the S&P 500 index was energy giant Exxon Mobil. By 2020, Exxon had slipped to 18th. Meanwhile the top five spots have been taken by Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Facebook and Google (Alphabet). Netflix, shaded red, with its impressive 4,000% ten-year return sits at number 34, ahead of both Walmart and McDonalds in terms of company value.

Certain uncertainty

Reflecting on a decade of mostly positive annual returns can somewhat mask the economic and political events thrown at investors.

It’s easy to forget how close the Eurozone came to suffering a widespread sovereign debt crisis. First Greece, then Spain, Portugal, Italy and Ireland ran out of money.

It wasn’t long before the idea of an in/out EU referendum was being floated by David Cameron. That idea came to full fruition in 2016, and months later Donald Trump was elected the 45th US President.

Elsewhere in the world, there was a recession in Japan, slowing growth in China, escalating trade wars, geopolitical turmoil in the Middle East, and the current Coronavirus outbreak.

Then over the course of 18 months, Swedish activist Greta Thunberg pushed climate change to the top of the global agenda. Having started campaigning with a solo protest outside a Swedish government building, she was most recently invited to speak in front of world leaders at Davos.

Navigating the years ahead

Which brings us to the present day and the first ego-check: no one will ever be able to predict precisely what will happen to markets over the next decade. As we saw last year, avoiding worst-case outcomes can be just as reassuring for investors as positive ones.

Rather than taking fright at the deceleration of economic growth in many parts of the world during 2019, markets focused on the potential kickback from lower interest rates and the resumption of monetary support from central banks.

The question is how long this formula will continue to fuel a relatively stable economic and investment environment. Remembering their cries of an imminent ‘double-dip recession’ back in 2010, the predictive power of economists should be kept in check.

We can learn from the barrage of uncertainty that investors have had to deal with over the last decade. It pays to ignore the noise and avoid making decisions based on fear or anxiety.

Staying rational and long-term sighted is a constant, worthwhile endeavour, and to some extent completely at odds with human nature. Evidence suggests the best outcomes are a result of setting longer term goals, clear strategies and a suitably diversified investment approach.

The spectacular rise of the technology giants, leapfrogging firms like Exxon in the oil sector, can teach us another lesson: it’s entirely possible the winners of today are not the winners of tomorrow.

NASA’s latest consensus assessment of climate change shows that at least 97% of scientists attribute warming trends to human activities. Against a backdrop of rising public scrutiny, it is almost inevitable that stakeholders of all types will have to play their part in addressing their wider environmental impact (climate or otherwise).

To that end, it seems some of the old rules of investing are being updated to recognise a broader set of risks. Companies increasingly need to demonstrate they are conscious of pollution as well as profit, communities as well as customers. The very notion of generating a “sustainable” return has taken on new meaning.

Whether it’s restrictions on combustion engines and plastic packaging, or shifting eating habits and energy efficiency standards, some trends are clear even today. Adapting to the changing needs of consumers, governments, and the planet, will be key to thriving in the 2020s – and beyond.

Important information

If you have any questions on the above or to find out more about our investment service, please call 020 7287 2225 or email hello@edisonwm.com.

This document does not constitute advice.

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future.

Edison Wealth Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. The company is registered in England and Wales and its registered address is shown above. The company’s registration number is 06198377 and its VAT registration number is 909 8003 22. This document does not constitute advice.

<< Back to Insights

Contact us to see how we can help.

+44 (0) 20 7287 2225

hello@edisonwm.com

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The information contained in this website does not constitute advice. The FCA does not regulate tax advice. The FCA does not regulate advice on Wills and Powers of Attorney. The Financial Ombudsman Service is available to sort out individual complaints that clients and financial services businesses aren’t able to resolve themselves. To contact the Financial Ombudsman Service please visit www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk.