In the national interest

12th August 2020

Between 10,000 and 2,000 BC, the middle-east region of Mesopotamia was host to some of the earliest advancements in human history. Nestled between Africa, Asia and Europe, the people there were the first to transition from hunter-gatherer to more efficient methods of food production using cultivation and stock breeding. This simple shift meant that for the first time ever, fewer people were needed to provide food. It allowed them to develop and specialise in the arts, law and science.

In the south-Mesopotamian civilisation of Sumer (in modern-day southern Iraq), experts have found the earliest known archaeological evidence of the wheel, astronomy, writing, cities, and the division of time into minutes and seconds. Thanks to the work of recent economic historians, we can recognise another Sumerian “first”: the concept of charging a rate of interest.

Recovered clay tablets from the era suggest that the default interest rate in 2,300 BC was 20%. Such an accurate assertion can only be made due to understanding Sumer’s sexagesimal (60-based) system of simple fractional counting and measuring.

One silver mina (a standard of weight) was equal to 60 shekels. Every month, interest would be charged at one shekel per mina owed. After 12 months, the repayment would stand at 12/60ths of one mina, otherwise expressed as 20%.

The principle of using the local fractional system to set interest rates continued with Greece’s dekate (1/10th, or 10% per year) and Rome’s troy ounce per pound (1/12th, or 8.3% per year). There is an elegant simplicity that sadly evades the modern approach to determining interest rates, and in recent years we have seen increasing attention paid to the unusual notion of negative interest rates.

Base rates

But first, it’s worth recognising that while interest rates are one of those dull realities of life, their impact reaches deep into the pockets of virtually every person and business in the country. As the UK emerges from its covid-19 lockdown, understanding what rates are for and where they may head is essential to understanding how the wider economy might recover.

When reading about ‘UK interest rates’ it’s usually in reference to the Bank of England’s (BoE) base rate. This is the interest that the high street banks like Barclays and Lloyds receive on their own cash deposited with the BoE. If the base rate changes, those commercial banks are then influenced to adjust the rates they offer on savings and charge in interest for customers.

So, after the central bank changes rates, it eventually trickles down to hit individuals via commercial banks.

Behavioural management

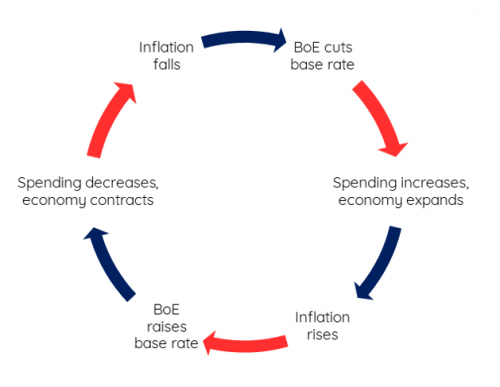

Changing the incentives around saving and lending money influences behaviour. Broadly speaking, as interest rates reduce, more people can borrow. All things being equal, this means more people spending, and if this extra money chases after the same level of goods there is an excess of demand over supply. The result is that prices increase (known as inflation).

The reverse is also true when rates rise, because both the incentive to save and the cost of borrowing is higher, which lowers spending. Too little inflation suggests people are sitting on their money, too much suggests the economy is overheating unsustainably.

The real primary agenda of central banks such as the Bank of England is therefore to manage inflation – interest rates are just one of its main tools.

It is possible to illustrate the decisions taken by central banks as part of the economic cycle, as shown above. In simple terms, economies are at all times positioned somewhere in the cycle but often with conflicting decisions to make.

Negative rates

As of August 2020, the BoE’s base rate stands at 0.10%. It’s a historically low level, leaving little room to fall further before hitting zero, or entering negative territory.

Even at the turn of the century, negative interest rates were something of a fantasy, with no one thinking they would ever exist in the real world. Sweden was the first country to take the plunge in 2009. Then in 2014 the European Central Bank was faced with the prospect of a deflationary spiral, with spending remaining stubbornly low despite already low rates. It cut to minus 0.10%, meaning European banks would be charged for holding money on deposit.

When rates turn negative the traditional banking model becomes inverted. Rather than earn interest on a deposit you effectively pay a storage fee. Since the ECB base rate dropped to minus 0.10%, commercial banks have been understandably hesitant to pass on the penalty to customers.

In theory, the same could apply to mortgage rates. A negative interest rate in this context would mean the amount owed would decrease every year. In 2019, Denmark’s Jyske Bank pioneered a mortgage of minus 0.5% per annum, although associated fees meant the real rate was positive.

There have been scarce instances of other institutions following Jyske Bank’s lead. Instead, when it comes to real world examples we have seen many more instances of negatively-yielding government bonds.

Negative rates vs negative yields

The UK government recently sold a negative-yielding three-year gilt (a government bond) for the first time. Yields in this context are an effective interest rate or return on an investment.

Buyers of the bonds are essentially paying to lend money to the government. Deeming them to be a safe haven asset, investors bought the three-year gilts knowing they would get back less than what they paid for them if held to maturity. In total, £3.8bn of bonds were bought at a rate of minus 0.003%.

Which begs the question – why would anyone invest in something they knew would return less than they paid for it?

There are a variety of reasons. Commonly, the investor will be an insurance company or pension fund who is more concerned about matching liabilities to current rates than predicting the future.

Institutional investors might also simply find themselves with a dwindling list of safe options for storing large cash deposits. Cash does not offer particularly attractive returns when base rates are low or negative. On the other hand, even negative-yielding gilts still offer the opportunity to be sold at a profit before maturity, should prices change favourably.

Where next for UK rates

The coronavirus-related contraction has dragged down inflation from 1.8% in January to 0.6% in June 2020. Economic output (GDP) meanwhile fell by 19.1% in the three months to May 2020. Looking back at the economic cycle, we appear to be firmly in the top left area of the chart. Conventional wisdom would suggest a rate cut is required, but by how far will depend on the seriousness of the economic decline.

Despite Sweden’s and the ECB’s experiments, there remains much debate about whether the BoE will also move to a negative base rate. In May 2020, BoE governor Andrew Bailey stated that negative interest rates were “under review”.

The main risk around negative rates is the imposition on the banking sector. They are left having to pay interest to the central bank, and as a result may keep both their saving and lending rates higher for fear of losing customers and profitability.

With the effectiveness of negative rates in question, it is uncertain whether we would see such a move in the UK. Instead, the BoE might first look to reduce rates to 0% and expand its quantitative easing (QE) programme.

Either way, it seems interest rates are likely to remain at historic lows for the time being. The task of behavioural management – difficult even in normal times – is complicated hugely by the pandemic. Perhaps the Sumerians had it right all along.

<< Back to Insights

Contact us to see how we can help.

+44 (0) 20 7287 2225

hello@edisonwm.com

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The information contained in this website does not constitute advice. The FCA does not regulate tax advice. The FCA does not regulate advice on Wills and Powers of Attorney. The Financial Ombudsman Service is available to sort out individual complaints that clients and financial services businesses aren’t able to resolve themselves. To contact the Financial Ombudsman Service please visit www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk.