This time, it’s about the destination

5th June 2019

Wall Street legend Benjamin Graham once proclaimed, “The investor’s chief problem, and even their worst enemy, is likely to be themselves.” He didn’t just say it to be rude. Humans are emotional and quite often irrational. No surprises there you might think. It’s a tenet in the field of behavioural finance but mostly absent from traditional economic theory. Understanding “economic man’s” behaviour matters. As we’ve written about before, behavioural bias can cloud financial decision-making and adversely affect investment returns. In his book “The Laws of Wealth”, Dr Daniel Crosby studied our inherent tendencies, tallying all the ways in which we are naturally disposed to being unconsciously influenced. He finished with a list of 117 biases. Being conscious of biases and how to mitigate them will help avoid irrational outcomes. To demonstrate why, consider some examples.

If you had to pay someone £100 for a single coin flip landing on tails, how much would you want to receive if it lands on heads? Chances are, the figure in your mind is quite a bit higher than £100. Probability theory tells us that any rational person should be happy with anything over £100. So why doesn’t an offer of £101 for heads seem worth the risk?

Let’s raise the stakes. Imagine for a moment that you’ve taken a seat at the roulette wheel. You start well, winning £1,000. But then your luck changes and you end up losing £800 from your winnings. At this point you call it quits, walking away with the remaining £200 you’ve won.

Then imagine you go back to the casino the following day. You quickly rack up a loss of £800. But this time your luck improves and the next few bets generate £1,000 so that, despite the initial loss, you leave up £200. Now, think about how you might feel after each day at the casino.

The average person reads about the first day’s experience and describes the discomfort at squandering most of their winnings. To have had £1,000 at one point and leave with £200 feels like a loss. Yet when thinking about day two, it feels different. Losing £800 immediately is painful, but to then recover those losses and leave with £200 ends up feeling like a triumph in the face of adversity.

Some sort of bias appears to obscure the economic fact that on both days we go home £200 richer. And with our £100 coin flip example, the statistics say we should be happy with a £101 pay out – except the vast majority of us aren’t. In other words, it’s not just about where you end up, but the emotional journey you took to get there.

It doesn’t just matter where you end up, but how you get there

Research has shown that the pain of losing is far greater than the satisfaction from equivalent gains. It’s a bias known as loss aversion, first documented in 1984 by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, and since demonstrated over and over again.

Kahneman and Tversky say that our attitude to loss falls into the brain’s intuitive mode of thinking, or what they creatively call System 1. This system can read the equation 2 x 2 and know that the answer is 4. It can meet someone new and instantly form a good impression. Or, it can see a loss at the roulette wheel (or in a valuation) and instantly feed us a set of negative emotions.

By contrast, System 2 is the logical, reasoned mode in the brain. If you read the equation 37 x 18 you are unlikely to know the answer without thinking hard about it. Kahneman and Tversky have found that system 2 may be rational but it is also lazy and works only if it really has to. Did you attempt to work out 37 x 18? Neither did we.

When confronted with a loss, Kahneman and Tversky say our emotional, intuitive System 1 takes over while the rational System 2 expends as little effort as possible.

At this point you may be wondering why an intuitive aversion to loss is a bad thing. Well, it is particularly important for long-term investors because almost all investments – including our portfolios – move up and down. Loss, or the prospect of loss, is an inherent part of investing.

Stock markets are well known to be volatile. Whether we analyse the UK or US, on an average day the chances of either stock market having a positive return is around 50%. Conversely, there’s also a 50% chance it will be down. What we know from loss aversion bias is that those down days will feel disproportionally bad when compared to the positive days.

Unlike a 50:50 coin toss, history shows us that the UK and US stock markets have grown considerably over the long-term despite negative returns on half of all days. It stands to reason that the positive days are greater in magnitude if not in frequency.

In reality investment managers will diversify their clients’ holdings across a range of assets that might include stocks and bonds from the UK, US and beyond. While investment portfolios tend to go up over longer time periods, on any given day, week or month the position may look worse.

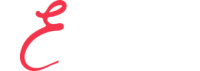

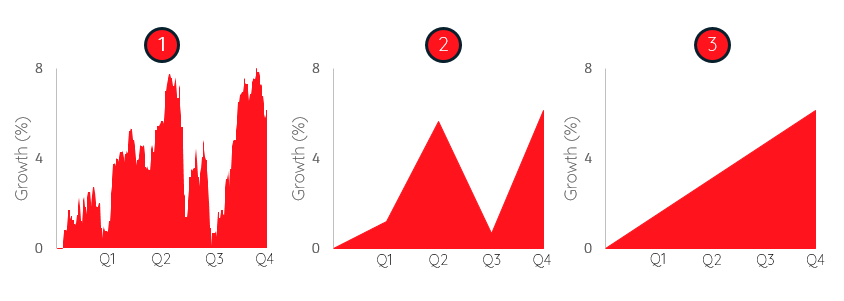

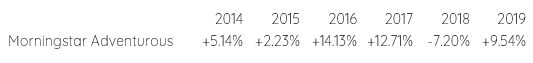

Consider the three charts above. Each show the same year in the recent history of Morningstar’s ‘Adventurous’ benchmark (in this case the year – made up of four quarters – to 30th June 2018).

Chart 1 shows the daily growth of the strategy. Over twelve months there are clearly dozens of peaks and troughs. An investor looking frequently at the changes would have felt the emotional toil of daily highs and lows. The problem is that over such short time periods they are not observing returns – they are experiencing the volatility of the portfolio first-hand.

Looking at the brief but steep drop in the third quarter (Q3), would that investor have let their aversion to loss affect their behaviour? The danger is that taking rash action has been shown to negatively impact the chances of reaching long-term financial goals – for instance by withdrawing money or adjusting the level of risk in the portfolio.

The good news – as you may have twigged – is that something simple can be done to avoid these dangers.

Chart 2 mimics the emotional journey of an investor who looks at the growth of the benchmark on a quarterly basis. Notice that it’s a much smoother ride. Dozens of troughs are now just one period of negative growth in Q3.

Lastly, chart 3 represents the growth experienced by an investor who checks once a year. They felt no loss during the year. They avoided the emotional rollercoaster. And crucially, they weren’t tempted to interfere to the potential detriment of their goals.

Given the choice, which path would you take? The evidence is clear that our financial and emotional health can benefit from a more sanguine and “hands-off” approach to checking investments. And hands-off doesn’t work unless there are clear objectives in place.

The important thing is not to ignore investment performance entirely – periodic reviews are worthwhile. But taking a long-term view of those investments can limit emotional distress.

We use a scientific approach to build a considered financial plan. And we make sure the tough decisions are made in System 2 mode – crunching the numbers and weighing our options. People often say life is worth it for the journey. That may be true. But when it comes to investing and staying on the narrow, rational path to achieving objectives, it’s all about the destination.

Important Information

If you have any questions on the above or to find out more about our investment service, please call 020 7287 2225 or email hello@edisonwm.com.

This document does not constitute advice.

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future.

All the performance data used in this report has been sourced from Morningstar and investment performance is calculated using Time Weighted Return.

The above graphs are for illustrative purposes only. They represent one year of returns from 01/07/2017 to 30/06/2018 for Morningstar’s Adventurous strategy, as displayed on a daily, quarterly and annual basis.

Edison Wealth Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. The company is registered in England and Wales and its registered address is shown above. The company’s registration number is 06198377 and its VAT registration number is 909 8003 22. This document does not constitute advice.

<< Back to Insights

Contact us to see how we can help.

+44 (0) 20 7287 2225

hello@edisonwm.com

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The information contained in this website does not constitute advice. The FCA does not regulate tax advice. The FCA does not regulate advice on Wills and Powers of Attorney. The Financial Ombudsman Service is available to sort out individual complaints that clients and financial services businesses aren’t able to resolve themselves. To contact the Financial Ombudsman Service please visit www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk.