Bitcoin or Big con?

7th February 2018

In our recent Insights piece ‘The Hidden Risk of Cash’, we opened with the question: what do you picture when you hear the word ‘money’? Had we asked any Briton born since the time of King Offa in the 8th century their answer would probably have referred to pound sterling – the world’s oldest currency still used today.

But since 2009, a new type of currency has emerged; one that is decentralised, meaning it’s completely detached from banks, governments or any other single point of institutional control. From the long list of these burgeoning ‘cryptocurrencies’, Bitcoin was the first and now most recognised example.

What is Bitcoin?

In essence, it is a totally digital currency, born out of the distrust of banks following the 2007-08 financial crisis. As such, it has a number of fundamental differences to traditional, or ‘fiat’ (government issued) currencies. The ‘coins’ (or fractions thereof) are created, transferred and recorded in the ether of the internet – more specifically, via the core Bitcoin software which is run on tens of thousands of computers around the world.

How does it work?

When we buy things in a supermarket in the usual manner, we can be sure of two things: that the notes or coins we hand over are received by the shop and the items placed in the basket are the ones we will be taking home.

With digital assets it is much harder to reliably establish who owns what at any point in time, because non-physical things like documents or images can be easily copied.

Bitcoin’s anonymous inventor(s) – going by the name Satoshi Nakamoto – recognised that their idea for a new digital cash system would need to solve this duplication (or “double-spending”) problem without relying on a central body to oversee the process.

The answer was to create a unique type of public ledger for transactions and ownership. Each new transaction would be added to the lists of records, called ‘blocks’. When linked together, these blocks comprise the ‘blockchain’.

The revolutionary part of this technology was that the validity of each transaction was reached by consensus. In the case of Bitcoin, if any user tried to send more coins that they actually owned, the network of computers running the Bitcoin software would recognise the error and agree to reject the transaction. Conversely, valid transactions (as determined by consensus), would be added to the blockchain.

The network of computers that enable Bitcoin to exist are called ‘miners’. Nakamoto incentivised people to be part of this network by rewarding them with new coins for completing the mining calculations.

The difficulty of these calculations has been intentionally programmed to rise incrementally, resulting in a diminishing supply of new Bitcoins over time.

Despite there being a public record of every Bitcoin trade, cryptography anonymises every user of the system. In any one transaction, all that is visible to an outsider are the two strings of 34 alphanumeric characters representing the sender and recipient, as well as the number of Bitcoins being transferred.

‘Cryptography anonymises every user of the system.’

Users create an electronic Bitcoin ‘wallet’, which acts a bit like an email address, providing them with a place to store and receive coins.

How do you buy/sell it?

Today, most buying and selling takes place on the many Bitcoin exchanges. Here individuals can exchange their conventional currency for cryptocurrency and vice versa. The initial process can be surprisingly difficult and expensive. Popular services such as Coinbase have experienced regular outages and delays as they struggle to process record numbers of new accounts.

Buyers wishing to exchange smaller sums, or those simply searching for a more familiar transaction, may have visited one of a growing number of ‘Bitcoin ATMs’ dotted around the UK. Requiring only a wallet address and a form of sterling payment, they sell at an above-market rate in return for their convenience.

What are Bitcoin’s proponents saying?

Bitcoin is the original fully-decentralised electronic payment system. For the first time in history, blockchain technology allows ‘money’ (in the form of a Bitcoin) to be sent electronically to anywhere in the world without relying on a third party. Many cryptocurrency supporters point to the 2007-08 financial crash as an example of where single points of control and oversight failed to prevent a global crisis.

And recently there have been many examples of centralised controls on access to capital and money. In 2015 for instance, the Greek government imposed strict capital controls on bank account holders. Cash withdrawals were limited to €60 per day and international transfers restricted. Bitcoin is quite simply immune to this type of intervention.

There are no limits or restrictions on the number of coins that can be sent in any one transaction. Equally, because the recipient is identified only by a string of letters and numbers, there aren’t any geographical restrictions on where coins can be sent either.

Unlike a traditional bank account, Bitcoin wallets can be opened by anyone in any location with an internet connection. There are no forms to fill out or identity checks to complete. It is thus referred to as a permission-less system.

‘Bitcoin wallets can be opened by anyone in any location with an internet connection.’

The scarcity of Bitcoins (there will only ever be 21 million in existence) means their value cannot be inflated away through increases in supply. This feature stands in contrast to the use of quantitative easing (a type of money printing) by central banks over the last decade.

In theory at least, Bitcoin transactions are designed to be low-cost and confirmed by the miners in minutes. Microsoft and Expedia are part of a modest but growing list of places accepting Bitcoin payments.

What are the critics saying?

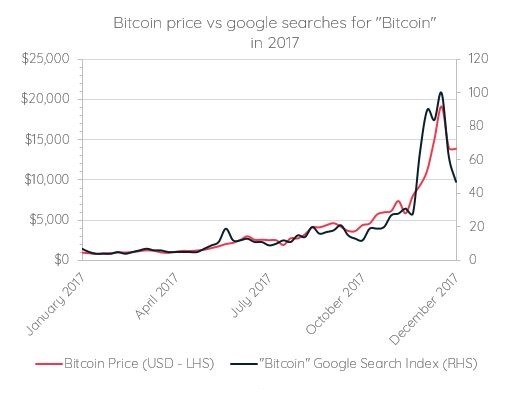

One of the most popular Google searches of 2017 was “Should I invest in Bitcoin?” The question itself presents the interesting notion of whether Bitcoin is a currency or an investment.

As a currency, Bitcoin presents a number of fundamental drawbacks when compared to pounds or dollars. Last year, the price of one Bitcoin rose by 15,000% and continues to fluctuate wildly on a daily basis. It makes it difficult for sellers denominating their goods or services in Bitcoin to know what to charge from one day to the next. Likewise, it becomes much harder for people buying things with Bitcoin to plan their expenditure.

Yet Bitcoin has overwhelmingly been treated as an asset first and currency second. Its huge rise in value during 2017 led to simple hyper-deflation; in Bitcoin terms, the cost of goods and services was getting cheaper and cheaper. Thus there was incentive to hoard more and more coins, pushing its value even higher. Why would anyone actually spend their “money” on anything if they could buy 20% more with it tomorrow?

To some extent the value has been driven higher by the idea of limited supply, but the notion of scarcity may well be a misnomer. Although there will only be 21 million Bitcoins in existence, there is nothing to prevent an infinite number of new cryptocurrencies from being launched.

Transaction fees are now often in excess of $20 and completion times are hours, rather than minutes. Bitcoin’s current maximum rate of seven (7) transactions per second is massively dwarfed by VISA’s 50,000 capacity. Bitcoin’s success is being undermined by its inability to cope with a high volume of transfers – the technology has never been stress-tested to this extent.

Running a network by consensus means that technological changes are almost impossible to bring about. The innovation to improve Bitcoin’s operational limitations already exists, it just takes the majority of users to agree to its implementation.

In many ways the appeal of the mining reward is creating a wasteful arms race. Today’s best estimates put Bitcoin’s total energy use at a staggering 0.2% of the world’s total consumption. If Bitcoin was a country, it would be the 53rd highest energy-consuming nation on earth.

One of the selling-points of Bitcoin is the removal of counterparty risk because transactions are irreversible and there are safeguards on double-spending. The rise in popularity of cryptocurrency exchanges have reinjected the element of counterparty risk back into the equation. From stories of insider trading to instances of hacked Bitcoin wallets and accounts, some users are finding out the hard way that decentralised and unregulated markets are a double edged sword.

What does the future hold?

Many of the loudest proponents of Bitcoin unsurprisingly stand to gain from its growth. In recent weeks and months the number of people forecasting it will hit $1m has been mirrored by those warning of its imminent demise. Missing out on the exponential growth feels painful. But holding an asset when the bubble bursts can be incredibly humbling.

Bitcoin’s value relies on it being accepted as a currency, which leaves it vulnerable to changes in legislation. In the UK, banks are generally nervous about accepting transfers from crypto exchanges or businesses. Government-imposed regulation could easily hamper efforts to grow the scale of adoption.

Bitcoin is a long way from being a viable alternative to fiat currency. It has, however, been the first successful experiment in the use of blockchain as a public ledger.

When it comes to the success of cryptocurrencies, it’s hard to find two more critical advantages than technology and scale of adoption. As transaction costs have skyrocketed and processing times soared from seconds to hours, new currencies have tried to find better ways of implementing blockchain technology. Promises of cheaper fees, instant transfers or even more anonymous interactions have given rise to Bitcoin’s lesser-known competitors: ‘Ethereum’ has its smart-contracts, ‘Ripple’ is, somewhat ironically, aimed at financial institutions, and ‘Litecoin’ claims to be simply a better Bitcoin. These are just a few of the c. 1,400 coins and tokens circulating in 2018. Crucially, all of them rely on the blockchain.

‘In the world of crypto-economics, the rules of the game haven’t been worked out yet.’

In the world of crypto-economics, the rules of the game haven’t been worked out yet. In 20 years’ time it’s unlikely that all of the cryptocurrencies currently available will still exist. It is also hard to argue with the notion that the current regime is driven by sentiment and narrative, rather than fundamental value. The crypto future depends on finding real value, not just words or promises, in order to produce a stable and viable currency.

Important Information

If you have any questions on the above or to find out more about our investment service, please call 020 7287 2225 or email hello@edisonwm.com.

This document does not constitute advice. The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future.

The above charts are for illustrative purposes only. The graph relates to the period 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2017. Where referred to, google searches are measured using the Google Trends search popularity index (trends.google.com/) and the Bitcoin price is measured using data from Coindesk (www.coindesk.com/price).

Edison Wealth Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Bitcoin is not a regulated investment.

Contact us to see how we can help.

+44 (0) 20 7287 2225

hello@edisonwm.com

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The information contained in this website does not constitute advice. The FCA does not regulate tax advice. The FCA does not regulate advice on Wills and Powers of Attorney. The Financial Ombudsman Service is available to sort out individual complaints that clients and financial services businesses aren’t able to resolve themselves. To contact the Financial Ombudsman Service please visit www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk.