Who cares about inflation?

20th May 2021

The 12th April 2021 was a day of relief and celebration for many in England. It marked the first time in months that people could sit outdoors at pubs and restaurants, take domestic holidays, and perhaps most urgently for many of us, get a haircut.

The gradual relaxing of restrictions has brought with it questions around how the economy will react to shoppers hitting the high street. One mooted change is that a period of inflation is to come. As the salons fill up, and with more ‘reopening’ on the horizon, we’re reminded of the late US author Sam Ewing, who said:

Inflation is when you pay $15 for the $10 haircut you used to get for $5 when you had hair

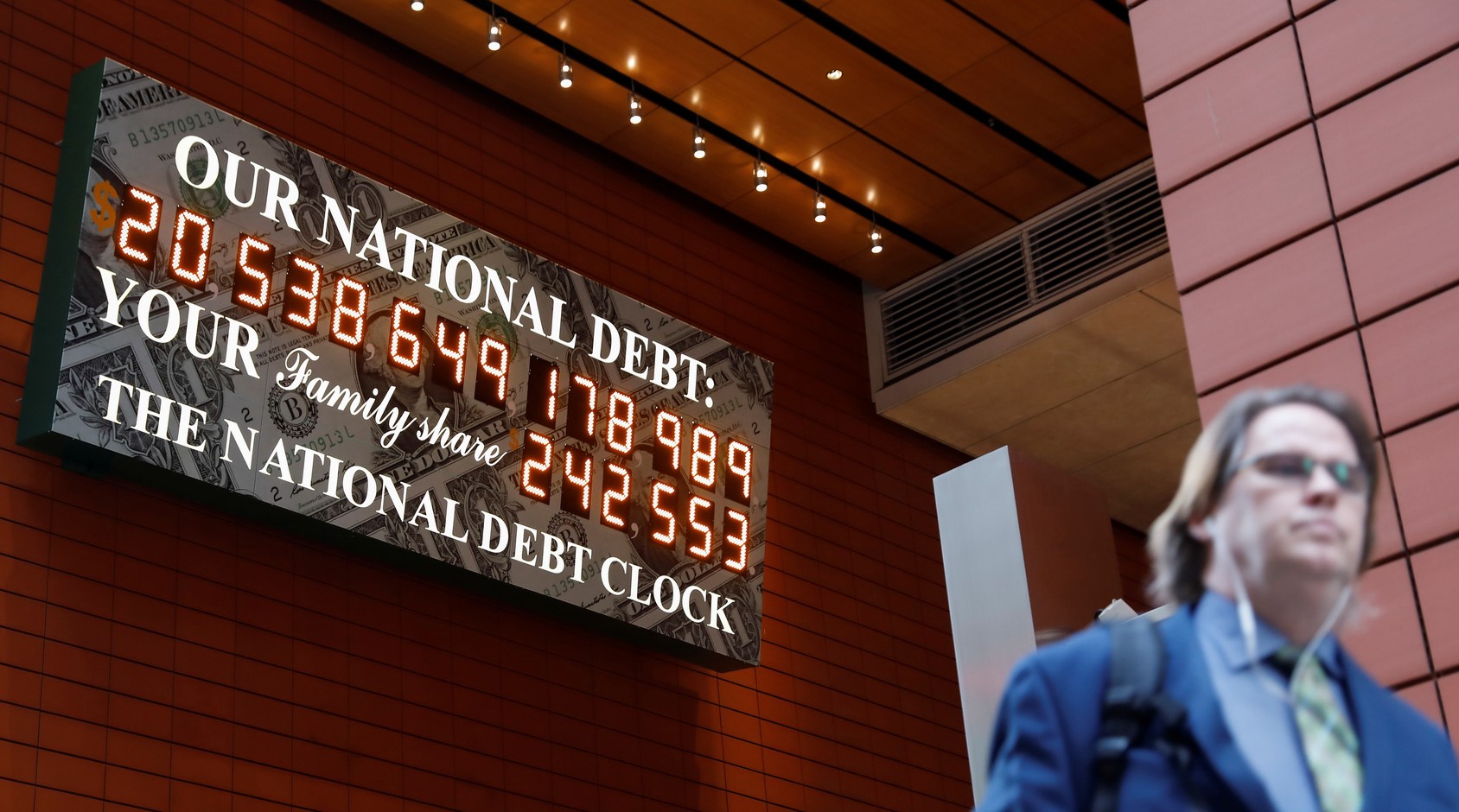

Ewing has captured the essence of inflation: prices rising over time. In the UK, we generally use a basket of goods and services (such as food, transport, and recreation) known as the CPI (the Consumer Prices Index). For all the talk of inflation and indexes, a crucial element is often missing when explaining why it matters.

Rising prices are not necessarily bad. After all, the Bank of England targets an annual CPI increase of 2%. In the last three decades CPI has been within the Bank’s tolerance levels; we have been spared long period of excessive inflation. The same can be said for most developed countries. As the UK and much of the world emerges from the pandemic there are concerns that the thirty-year hiatus could come to an end.

There are some compelling arguments, given governments and central banks have spent the last year trying to prop up businesses, jobs, and the broader economy.

The first theory, known to economists as Keynesianism, argues that supply and demand imbalances will cause inflation. Over the last year, UK households have built up savings well above historical averages. Once people start spending, the demand for goods and services could pull prices higher. Equally, businesses may find they need to hire more staff which can cause wages to rise as unemployment falls.

The recent Suez Canal blockage is an apt metaphor for lockdown-induced supply chain interruptions and underproduction. As anyone who has tried to buy garden furniture recently will attest to, when the supply of goods or raw materials is reduced, costs can rise, pushing up inflation.

The second theory, Monetarism, argues that inflation could arise from an increase in the supply of money. Quantitative Easing (QE) is a central bank facility to increase the money supply. During the financial crisis of 2008-09, central banks used QE extensively to inject liquidity into the banking system. Again, in dealing with the Covid crisis, the BOE has resorted to QE by buying up bonds, effectively giving new cash to the bondholders.

Regardless of the mechanism by which inflation may occur, there is a range of potential consequences.

Inflation erodes spending power

For savers and consumers, inflation erodes spending power. The pound in your pocket will buy less today than it did 10 years ago. The key is therefore to maintain purchasing power over the long-term, which may be hard to achieve when interest rates are low. Simply put, higher interest rates can act as breaks on economic growth, thereby slowing inflation.

For businesses, inflation can mean prices become more volatile. This makes it harder to plan for the future, harder to predict what costs or sales might be, and therefore deters investment. Long-term decisions become a finger-in-the-air exercise.

For investors, the impact of inflation, particularly when climbing steeply, is potentially wide-reaching.

Traditional bonds like Gilts are inflation-sensitive because they pay out a fixed amount. Where a bond has a fixed coupon (or interest payment), the real value of the coupon will be less if inflation runs high. In these circumstances, the BOE has historically used higher interest rates to bring it down. But higher interest rates in turn make bonds less appealing because of the better return offered on cash deposits.

Higher inflation requires higher investment returns

At moderate levels, inflation is a sign of a healthy, growing economy. However, it also means the value of money declines over time. Investors will seek out higher returns from their investments to keep up with a higher rate of inflation. Over time, investors may look away from assets like bonds and cash, with typically lower longer-term potential returns.

Today, economists, central banks, and governments are conflicted about whether inflation will spike or for how long. The BOE predicts a move towards its target, the Fed thinks a spike will be short-lived. Given the lack of clarity, our view is that it remains prudent to favour diversification.

Trying to accurately time economic changes with significant shifts in portfolio allocations can have highly adverse effects on performance. Our strategies hold a range of assets and approaches that aim to protect against inflation.

The first feature is a minimal cash position. Cash is useful for liquidity and as a ballast in volatile markets, but in low-interest rate environments the interest often fails to keep up with inflation.

Commodities such as gold can offer some protection because of its limited supply and store of value. The price of commodities is also often linked to inflation, favouring companies with exposure to natural resources. Emerging market and UK large-cap equities include a number of these companies.

More generally, equities have typically performed well relative to inflation because companies are able to raise their own prices to match. This tends to be most effective over the long-term.

Certain types of bonds, known as Index-Linked Bonds, have their principal (underlying value) and coupon payments linked to a general price index. As an inflation hedge, these are most effective when inflation rises faster than expected.

And lastly, over the last two years we have increased allocations to renewable energy and infrastructure. Renewable input costs are low or zero, and revenue is often supported by government-backed price guarantees linked to the cost of living.

Ultimately, these strategies are about ensuring that investments keep up with changes in everyday prices – regardless of whether it’s healthcare, hazelnuts, or haircuts.

<< Back to Insights

Contact us to see how we can help.

+44 (0) 20 7287 2225

hello@edisonwm.com

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The information contained in this website does not constitute advice. The FCA does not regulate tax advice. The FCA does not regulate advice on Wills and Powers of Attorney. The Financial Ombudsman Service is available to sort out individual complaints that clients and financial services businesses aren’t able to resolve themselves. To contact the Financial Ombudsman Service please visit www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk.