The dollar dilemma

7th August 2025

The dollar’s reserve-currency role began with the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement. That system fixed most major currencies to the dollar, while the United States pledged to convert dollars into gold at a set price. In 1971 – confronted by widening US deficits and a dwindling gold stock – President Nixon suspended convertibility, severing the dollar’s gold link and opening today’s era of floating fiat exchange rates.

Over the ensuing half-century – accelerating after the 2007-8 global financial crisis – the dollar has climbed to heights few envisaged in the early 2000s, buoyed by stronger US growth, higher real yields and its enduring status as the world’s ultimate haven asset. Crucially, this resilience rests on the very economic framework the United States has helped to shape over decades.

The US has simultaneously propelled and profited from liberalised trade, open markets, fluid capital and labour flows, and a supportive (low tax) fiscal stance. As issuer of the world’s reserve currency, it dominates global payments, commerce, and foreign-exchange reserves. Favourable business conditions (light regulation) alongside top universities, skilled immigration, a flexible labour market, and abundant inward investment have enabled the US to sustain sizeable fiscal and current-account deficits. Consequently, US asset returns have eclipsed those elsewhere and the dollar has remained in demand. In sum, global exposure to US assets has intensified over time.

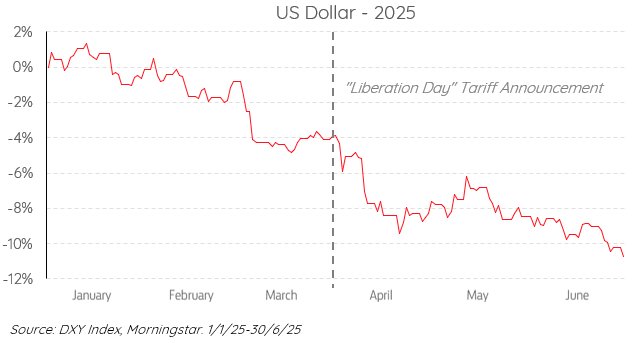

That prolonged ascent, however, has left the currency richly valued and more exposed to policy missteps. The Trump administration has ushered in heightened political, economic and market volatility. Protectionism, trade disputes and planned reductions in foreign aid threaten to raise prices, dampen growth and deepen uncertainty.

The consequence is that investors are now raising questions over the dollar’s reserve-status privilege and the role of US Treasury bonds in portfolios is being reassessed. As illustrated in the chart below, the DXY index, which measures the US dollar against a basket of six major peers, fell 10.7% in the first half of 2025 as confidence waned1.

Fractures in the dollar framework

Confidence in the greenback has traditionally rested on three pillars: policy neutrality, fiscal discipline, and an independent Federal Reserve. All now show signs of strain. Washington’s readiness to wield tariffs, export controls and sanctions has diluted perceptions of the dollar as an apolitical medium of exchange. Federal debt has climbed beyond 120% of GDP2, raising doubts about the sustainability of US public finances. Meanwhile, ever louder commentary from Capitol Hill about interest-rate policy risks blurring the once clear line between the Treasury and the Federal Reserve.

Evidence from global capital flows

Shifts in the global capital flows hint at a moderate diversification of reserve assets and settlement currencies. Japanese investors – formerly the largest foreign holders of US Treasuries – are finding yen‑denominated bonds more appealing as domestic yields rise, while higher government spending in Europe is starting to attract capital back towards the continent.

Central banks – led by China and a sanctions-encircled Russia – have doubled gold’s share of official reserves in the past decade, favouring an asset immune to payment bans and balance-sheet dilution. Commodity markets are also adjusting. Since 2022, a meaningful proportion of Russian crude has been invoiced in roubles, yuan or dirham, illustrating that non‑dollar payment channels can function when geopolitics demands it.

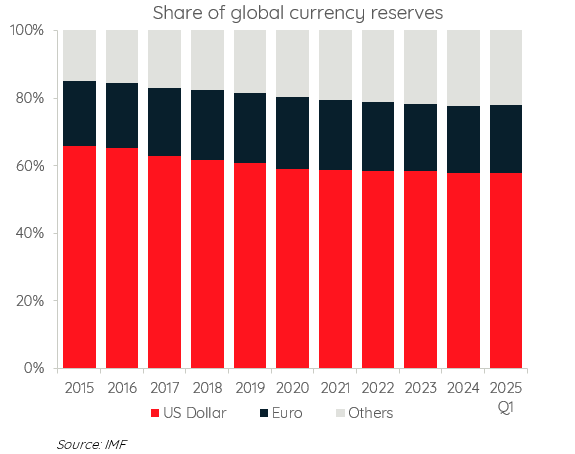

Meanwhile the share of US dollar reserves held by central banks fell to 57.7% in the first quarter of 20253 – its lowest level in 30 years, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). As the chart below shows, demand has been falling consistently over the last 10 years. In its place, the share of other currencies, including the Australian dollar, Canadian dollar, Swiss franc and Chinese renminbi, has risen.

Implications for sterling‑based investors

The most pressing question lies beyond the typical, sentiment-driven fluctuations in currency demand, to whether a structural shift in the dollar’s global role is underway. And importantly, what does the threat of “de-dollarisation” mean for portfolios?

Together, we view recent trends and challenges as partially eroding the aura of invulnerability that has served the US dollar for decades. Yet suggestions that it will lose its reserve-currency status are premature. Because the dollar is already the currency most widely used for payments and reserves, it creates a self-reinforcing network effect that is not swiftly undone. Combined with the unrivalled depth of US capital markets and the dollar’s pivotal role in global trade, this leaves no credible successor ready to take its place.

Reserve status does not insulate the greenback from cyclical setbacks as we have witnessed in the first half of 2025. President Trump’s unpredictable stance on trade, security and fiscal matters may impose a persistent headwind to the US currency. This has implications for the way we are approaching portfolio construction.

Dollar-related risks have unquestionably risen. To mitigate them, we are increasing sterling hedging within our global bond allocation. Hedging is simply a way to remove the effect of currency swings. This reduces the impact of any sustained dollar weakness on fixed income returns while still leaving an element of dollar protection during market stress.

By contrast, we continue to leave dollar-denominated equities unhedged; the relative impact of currency risk is smaller, often offsets over multi-year horizons, and the underlying companies earn a significant share of revenues overseas.

Managing risk is, as ever, an exercise in balance. We therefore maintain broadly diversified portfolios that span non-US markets and alternative assets – such as gold – to cushion against a weaker dollar, a resurgence of inflation, or a rotation away from US assets.

If you have any questions on the above or to find out more about our investment service, please call 020 7287 2225 or email hello@edisonwm.com.

Important information

This insight piece does not constitute advice.

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future.

Insight piece sources:

1 Morningstar

2 Federal Debt: Total Public Debt as Percent of Gross Domestic Product. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/gfdegdq188S

3 IMF

Edison Wealth Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. The company is registered in England and Wales and its registered address is shown below. The company’s registration number is 06198377 and its VAT registration number is 909 8003 22. The Financial Conduct Authority does not regulate tax planning or trusts.

The information contained within this insight piece is based on our understanding of legislation, whether proposed or in force, and market practice at the time of writing. Levels, bases, and reliefs from taxation may be subject to change.

<< Back to InsightsContact us to see how we can help.

+44 (0) 20 7287 2225

hello@edisonwm.com

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The information contained in this website does not constitute advice. The FCA does not regulate tax advice. The FCA does not regulate advice on Wills and Powers of Attorney. The Financial Ombudsman Service is available to sort out individual complaints that clients and financial services businesses aren’t able to resolve themselves. To contact the Financial Ombudsman Service please visit www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk.