The numbers that count

31st October 2025

There seems little doubt that the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rachel Reeves, faces a difficult November Budget. Low growth, weak productivity, sticky inflation and tight fiscal rules constrain her room for manoeuvre. Households still feel the squeeze from elevated prices and a high tax burden, while business investment has been depressed for years.

The outlook is not catastrophic, but a clear plan of action is now needed. At the heart of recent discussion has been a “black hole” in the public finances of at least £15bn – in other words, the shortfall between where the public finances are currently projected to be and where they must be to satisfy the government’s self-imposed fiscal rules1. High on Reeves’ priority list will be convincing the bond market that her policies are sound, given the government relies on borrowing huge sums to fund its spending.

Meanwhile, the US faces its own fiscal drama – a federal government shutdown that began on 1 October 2025 after Congress failed to pass stop-gap funding amid disputes over spending and healthcare. Many services are curtailed, and large numbers of federal workers are furloughed or working unpaid, while essential operations continue. The longer the impasse lasts, the greater the temporary drag on growth and the higher the policy uncertainty.

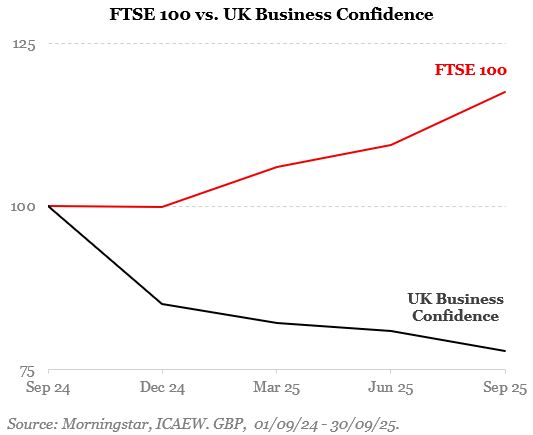

Even so, despite mounting concerns in both the UK and the US, equity markets have shrugged off the headlines and delivered positive returns – a reminder that markets and economies often tell starkly different stories.

As the above chart shows, in the 12 months to September 2025 business confidence in the UK steadily deteriorated while the FTSE 100 climbed to new highs. To understand that disconnect, it is worth exploring the role of monitoring economies.

The economy

We monitor the economy to understand how the country is functioning day to day. We want to know whether people are finding jobs, whether pay is keeping up with prices, and whether public services are coping with demand. We look for signs that shops and factories can fulfil orders without delays or shortages. We also assess whether government policy is helping living standards to improve or storing up problems for the future.

This information helps businesses plan hiring and investment. It helps banks judge the likelihood that loans will be repaid. It informs debates on tax, infrastructure and regulation. Above all, it tells us about the health of the system we all rely on.

The main pitfall is that most economic data is backward looking. GDP (Gross Domestic Product) numbers arrive late and are often revised. Monthly figures can be noisy – affected by holidays, strikes or interim changes. One data point rarely tells the whole story. What matters is the pattern across several indicators and the direction of travel. In short, the headlines are snapshots, not the film.

One data point rarely tells the whole story

Policy also takes time to work. Interest rate changes bite only as mortgages reset and companies refinance – typically over many months, not days. Tax rises or new spending alter behaviour only once households and firms adjust. The sequence is clear even if the timing is not – policy today, behaviour tomorrow, then any changes measured later. Good decision-making allows for these lags rather than reacting only when they show up in the statistics.

Most importantly, economies and markets are different things. Economic releases describe what has happened, but markets price what investors expect to happen. That is why weak data do not always mean weak market returns.

Markets

Markets look ahead. Prices reflect what investors think will happen to earnings, interest rates, risk and so on. They move when expectations change, rather than when the latest fragment of data is confirmed. This is why equities often move higher months before a recession ends and well before GDP growth speeds up again. Markets are concerned with the value of future cash flows in the policy regime to come, not the rear-view mirror of last quarter’s figures.

Because markets are forward looking, they can rise even when the economy appears vulnerable. A lacklustre data reading can be “good news”. If investors believe the slowdown will be short, that inflation is easing, or that policy will soon turn supportive, prices can rise even while the news flow still looks gloomy. And vice versa, strong data can pull markets down if it implies tighter policy or pressure on profit margins. Often the surprise versus what was expected matters more than the headline level.

Weak data can be good news for markets

There are practical reasons for the disconnect between the UK economy and its stock market. Many large UK-listed companies earn most of their revenues overseas, so global demand and the sterling exchange rate matter more than domestic GDP. Meanwhile, the types of businesses listed in the UK happen to be in defensive cash-generative sectors which have tended to prove resilient to global weakness. There is certainly no AI bubble here – only 1% of the UK stock market is in tech.

Prices also reflect judgement and human behaviour. At any moment, the market price is the consensus view of many investors about long-term earnings and the probability of achieving them. That consensus is imperfect. It is influenced by psychology – fear and optimism, recent experience, herd behaviour – and by practical constraints such as liquidity, risk limits and index flows. In the short run, these forces can push prices away from underlying value and out of line with the economic backdrop.

Disciplined investors keep both pictures in view. Economic analysis frames a range for fundamentals over the short-term. Market analysis shows what is already priced in. When the two diverge – gloomy data but improving markets, or upbeat releases alongside stretched valuations – the task is to judge whether prices reflect a credible future or temporary sentiment. Holding that distinction in mind supports patient, probabilistic decisions rather than headline-driven reactions.

November’s Budget

Ahead of the Autumn Budget, headlines are driving speculation about what might change. As we have pointed out before, acting on rumours can harm financial outcomes – the 2024 Budget showed that many predicted measures never appeared. Taxes are expected to rise, but which taxes – and by how much – is not yet known. After the Budget ritual is done and the Red Book is on the table, our website will set out what has changed and what has not. Once the fine print is settled, we will read the tables, do the sums, and set out on an individual basis the sensible next steps where required.

If you have any questions on the above or to find out more about our investment service, please call 020 7287 2225 or email hello@edisonwm.com.

Important information

This insight piece does not constitute advice.

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future.

Insight piece sources:

Chart – Morningstar, ICAEW UK Business Confidence Survey. GBP, rebased to 100, 01/09/24 to 30/09/2025.

1 https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-march-2025/

Edison Wealth Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. The company is registered in England and Wales and its registered address is shown below. The company’s registration number is 06198377 and its VAT registration number is 909 8003 22. The Financial Conduct Authority does not regulate tax planning or trusts.

The information contained within this insight piece is based on our understanding of legislation, whether proposed or in force, and market practice at the time of writing. Levels, bases, and reliefs from taxation may be subject to change.

<< Back to InsightsContact us to see how we can help.

+44 (0) 20 7287 2225

hello@edisonwm.com

The value of investments and the income arising from them can go down as well as up and is not guaranteed, which means that you may not get back what you invested. Past performance is not necessarily a guide to the future. The information contained in this website does not constitute advice. The FCA does not regulate tax advice. The FCA does not regulate advice on Wills and Powers of Attorney. The Financial Ombudsman Service is available to sort out individual complaints that clients and financial services businesses aren’t able to resolve themselves. To contact the Financial Ombudsman Service please visit www.financial-ombudsman.org.uk.